Daily they would vainly storm,

Pick and shovel, stroke for stroke;

Where the flames would nightly swarm

Was a dam when we awoke.

Human sacrifices bled,

Tortured screams would pierce the night,

And where blazes seaward spread

A canal would greet the light.– Goethe, Faust, 11123-30, (from Berman, p.64) ¹

Marshall Berman, who published a humane account of urban and literary modernism in 1981 called All That Is Solid Melts Into Air, died this week, on September 11, 2013 – the 12th anniversary of the Twin Towers destruction, and the 40th anniversary of the US-sponsored coup d’etat inaugurating bloody repression in Chile, the regime of General Pinochet. Seeing the many tributes that have been springing up over the last week, I decided to add mine as well.

1

When Berman’s book was first published, I was in between having finished an undergraduate degree in the history of art and what to do next. I was working then in a bookshop across the main avenue facing the western entryway onto the university campus. When the owner pulled the plug on the shop, All That is Solid was a parting gift handed to me by the last store manager who had observed me coveting it.

That was a good year for me in some ways; there were growing pains, sorrowful losses, a broken end to a school-years romance; but new post-university friends, and some dawnings. Liberating uncertainty at emerging little by little from the cocoon of schooling may have brought me my first affirmative experience of living more or less in an unknowing impasse, an unplotted state of managing by intuition and doses of self-mockery. With preset paths temporarily obscured, I entered into a less anxious now, with less of the sense of dread and deferred threat that has become a more pervasively dominant genre of living here since multiple cycles of crises, 9/11, and the collapse of the neoliberal economy from 2008. Today, I perceive much more firmly the mode of living of what Lauren Berlant identified as the falling man.² Still, in the first years of Reagan, we already knew that the storylines of our youth had long-since switched momentum; but I didn’t yet know just how steeply the ground would rise up in front of us.

2

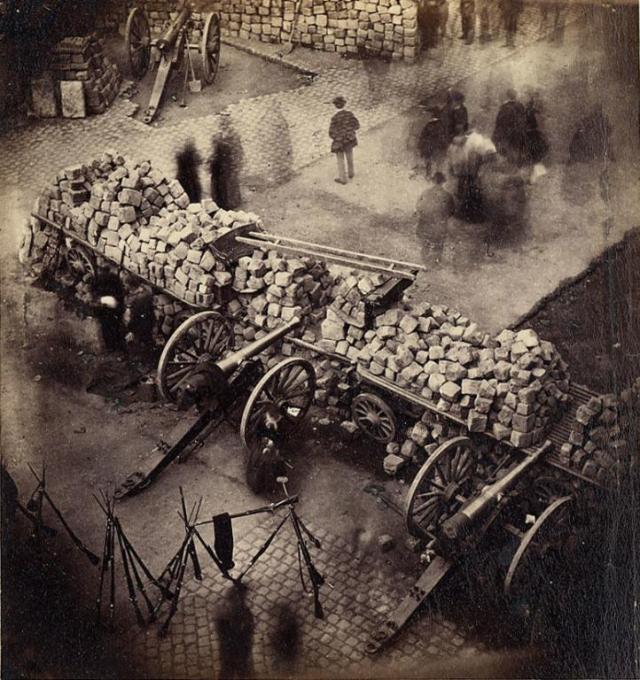

I hadn’t yet experienced life in the roiling swelter of a real city either. I caught a glimpse in Europe in the late 70’s, where I viewed its unraveling possibilities from a provincial Italian town where time hadn’t quite yet accelerated. Two or three years later, Marshall Berman’s dark blue book gave me a glimpse of things I still couldn’t know without leaving the bosom of my college town. Echoing back the structures of feeling of more than two centuries of urbanization and creative destruction, the book evoked the voracious forces and tragic losses of modernization, the brainings and hammer blows of urban development through memories of art, poetic literature, Goethe and an American Mephistopheles in the person of Robert Moses, wielder of a meat axe of transformational power over New York. Faust, the consumate wrecker and creator, inspired by greed and visions, created on the crumbling crust of fallen empire “reclamation projects” so exhausting and violent that even the devil catches himself overwhelmed by their novelty and savagery. Threading through the book’s various chapters, Hausmann’s Paris boulevards echo this flattening history forward, creating space both for the glitter and substitution inflicted on commodifiied streetscapes, where the nervous system of 20th century humanity lingers “isolated in the midst of wanderers.” The wide roads created new staging grounds for ongoing cycles of rebellion and defeat that still draw borders around convenient massing spaces in cities everywhere, where stone barricades can no longer obstruct moving rows of police batons and shields, but water cannons and tanks can seize spatial control.

3

For me, Marshall Berman’s All That Is Solid Melts Into Air confirmed and clarified the poetics resulting from the amorality and violence underlying the cycle of structure and destruction of cities that was always behind much of the art I loved. I had first had numerous occasions to understand the flattening of affect that Fredric Jameson later described as one of the defining characteristcs of late modern/ post-modern life, where cultural artefacts jumble into one another, losing the weight of significations on the way to becoming icons of absent history. But there was something alien and wonderful in these artefacts of modernism that remained remote and nostalgic (like steam punk). Every city-center street with a slightly long memory, every watering hole bar, cowboy pool hall, cafe, or remnant of an earlier, more artisanal form of commercially organized life my friends and I had ever loved had been threatened or swept away by the time I left the state where I was born. I had intuited in significant ways how easily the vascular connections that kept a past a vital participant in a present could be broken. But the easily-ruptured web that held the lives within cities together, bonded by ties of friendship and shared space, were a little beyond my youthful horizon then.

Even so, I couldn’t have known how delicate and fragile every link in the human chain would one day become. For that full realization I would thankfully have to wait. Witnessing the machinery manufacturing the decay of large cities was the first lesson in what punishments desire has to endure. Later still, it was Japan that entered my life, a butcher’s knifeblade at the throat of kinship.

4

Moloch who entered my soul early! Moloch in whom I am a consciousness without a body! Moloch who frightened me out of my natural ecstasy! Moloch who I abandon! Wake up in Moloch! Light streaming out of the sky!

– Allen Ginsberg, Howl

On discovering the news of Marshall Berman’s death, like everyone else I sadly pulled my copy of All That Is Solid Melts Into Air down from the shelf, and I found this in the preface.

My friends will know why this paragraph stopped me needing to read further:

‘Shortly after I finished this book, my dear son Marc, five years old, was taken from me. I dedicate All That Is Solid Melts into Air to him. His life and death bring so many of its ideas and themes close to home: the idea that those who are most happily at home in the modern world, as he was, may be most vulnerable to the demons that haunt it; the idea that the daily routine of playgrounds and bicycles, of shopping and eating and cleaning up, of ordinary hugs and kisses, may be not only infinitely joyous and beautiful but also infinitely precarious and fragile; that it may take desperate and heroic struggles to sustain this life, and sometimes we lose. Ivan Karamazov says that, more than anything else, the death of children makes him want to give back his ticket to the universe. But he does not give it back. He keeps on fighting and loving; he keeps on keeping on.”¹[b]

¹ Marshall Berman, All That is Solid Melts Into Air, Simon and Schuster, 1981.

² see Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism, Duke, 2011.

(Don’t miss the video clip below this picture of Rui of Marshall Berman talking about the decay and struggle for survival of New York. It’s inspiring!)

Brian, This is a beautiful piece. �Please don’t give back your ticket to the universe. �Thank you for introducing me to All That’s Solid Melts the Air. �You have been heard.

________________________________

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your always meaningful support Michele.

I think you would find Marshall Berman’s book inspiring. Let me know if and when you read it!

LikeLike

Very poetic & literary.

LikeLike

My sister is biased! 🙂

LikeLike

Keep on fighting and loving, my friend!

LikeLiked by 1 person

We have no choice, Tomas.

LikeLike