Unenforceability of Japanese Custody and Hague Abduction Convention Orders

Jeremy D. Morley*

[The following post by attorney Jeremy Morley is a short summary of the current (September 2017) legal circumstances with regard to child custody and international parental abduction in Japan. It amply illustrates why the most dire warnings possible can and should be issued by any and all institutions concerned with children’s well-being and the protection of children’s and parents’ rights, as regards any and all involvement with the Japanese family court system, or any circumstance in which a child is to be brought within the geographic area of Japanese territorial sovereignty.

Children’s rights to their parents, and parents rights to their children cannot and will not under any circumstances be protected by the Japanese state. Further, its supposed law-governed courts are entirely incapable of providing even a minimum of such protection to children, a fact often explained as the absence of any protective law in Japan under which assistance can be given. In this, Japan is an outlier and menace of the first order to all parents and children. NO CHILDREN should be allowed to pass into a geographic area of Japanese territorial sovereignty at any time, or under any circumstance, unless both parents are willing to accept the uniquely high probability that, should the relationship between the two parents encounter conflicts of any kind, the children can and are encouraged to be sacrificed by the Japanese state to the whim of the parent who has the superior advantage in the Japanese legal order: that is, the Japanese citizen with physical possession of the child. Children’s security, children’s safety from abduction, children’s continuing relations with and access to their parents, and parents’ relationships with and access to their children, cannot and WILL NOT be protected by any institution operating within the territorial sovereignty of the Japanese state. One can only conclude, therefore, that you must keep your children away from Japan.

This is not an idle warning, but a serious and very consequential one. The dangers awaiting families during, for example, the upcoming seasons of Olympics sports events in 2020, will increase. Abductions will occur; and the children will not be returned by Japanese authorities to the parent from whom they have been abducted. Keep in mind that there are roughly 3 million children in Japan today with no access to, nor communications with, their parent, due to the actions of the Japanese state, thus normalizing the practice among many if not all Japanese people, making it much more difficult for your pleas for justice and the safe return of your kids to be heard. Awareness of these numerous cases is very low there; but the sub-standard role of the courts in enabling and stimulating the problem is assumed in popular sentiment. That child and parent-protective law exists elsewhere that is enforceable appears to be unknown to most Japanese, who must assume that, shoganai, (translatable as “it can’t be helped, accept your fate”) nothing can be done about family-related conflict that breaks, terrorizes and destroys children and parents.

Japanese-partnered states, particularly the global sponsor to whom it is a client state, the United States of America, will not act to assist the return of your children should Japan decide to allow them to be abducted. There are numerous resources, including some earlier posts on this blog, explaining that the U.S. Department of State, in order to manage a growing problem with respect to fluidly global international parental abductions, created a subdivision/ special office (“Children’s Issues”) within the structure of its consular division, to assist in the deferral of action in child abduction cases. Under the pretense of providing assistance to parents, the Department of State has removed the immediate burden and potential linkages by which parents might attempt to obtain direct means within the national state to which abductions take place, and has created and layered on the procedural re-routing of parents’ cases, via global conventions, formalized processes, etc., whereby the process can be slowed, rendered ineffective, and eventually dropped in the interest of maintaining good state to state relations for private, financial and military interests in the United States and around the globe. The “best case scenario” that the U.S. offers its citizens, is that you pursue your case, privately and without assistance, in the Japanese family court system in which millions of child abductions have been “rubberstamped”, or ratified post hoc.

Not all of these issues are addressed in Morley’s piece below, but it does provide a solid piece of the narrative as it currently exists today for Japanese child abduction.]

The text from Jeremy Morley follows:

Child custody orders are not enforced in Japan. There is merely a provision for a fine, but it is usually de minimis and rarely employed. It does not impede a parent with physical possession of a child from denying the other parent access to the child. This is one reason (among several) why child custody is not shared in Japan and why visitation provisions are usually limited to short, periodic and often supervised meetings, unless the parents are genuinely agreed to provide otherwise. There is no court-ordered international visitation in Japan and overnight visits are rarely ordered unless the parent who possesses the child willingly agrees otherwise.

In July 2017, the Supreme Court of Japan issued a ruling in a custody case between two Japanese parents living in Japan. It overturned a most unusual and provocative lower court ruling that had provided for extensive visitation time for the father. Indeed, the Supreme Court ordered sole custody for the mother and adopted her proposal to permit the father to meet the daughter only once a month, since that was frequent enough for an elementary school student and more time with her father would be unduly burdensome on a child. The case was commenced seven years earlier, during which the mother had allowed the father to meet the child only six times. The decision to permit visitation of not more than once a month, and then only for a meeting, not for an overnight visit, is normal and typical in Japan.

When Japan agreed to adopt the Hague Abduction Convention (in 2014, some 35 years after it had been drafted and adopted globally), which provides for the court-ordered return of internationally-abducted children, the Government was required to make provision for the first time for enforcement of such orders. Accordingly, certain Japanese family lawyers worked extremely hard to draft enforcement measures that would, for the first time, lead to the enforcement of the terms of a Family Court order concerning children. However, their initial proposals were significantly diluted, and while the Diet ultimately adopted an extraordinarily lengthy enabling act bringing the Hague Abduction Convention into Japanese law, its provisions concerning the enforcement of Hague Convention return orders have proven to be unworkable.

Thus, in a case in Osaka in which the Osaka High Court ruled that four children, whose Japanese mother had abducted them from the United States, must be returned to their American father in the U.S. The father ultimately prevailed on so-called “enforcement officers” from the Nara District Court to make some efforts to enforce the return order, but when the mother refused to cooperate they declared that enforcement was not possible. Early this year, the Osaka court reversed its original return order and authorized the mother to retain the abducted children in her sole custody in Japan.

Just a few days ago, an advisory panel to the Japanese Justice Ministry proposed that some enforcement measures beyond mere fines should be enacted in order to enforce orders in domestic custody cases, and it suggested that, after public comments, the matters could be submitted to the Japanese Diet “as early as 2018.” Whether any such law will ever be enacted is entirely uncertain. And whether any enforcement measures that are enacted will themselves be enforced in practice is even more uncertain.

In the meantime, the basic approach continues, whereby Japanese child custody cases merely “rubberstamp” the principle that whichever parent has physical possession of a child may in practice decide whether or not to allow the other parent to see their child. And since physical possession means everything, parents who do not fully trust the other parent to return the child are necessarily reluctant to part with possession for even a day, which explains why visitation in Japan is generally limited to intermittent short supervised daytime meetings in a secure location.

Published Thursday, September 21, 2017 at:

http://www.internationalfamilylawfirm.com/2017/09/unenforceability-of-japanese-custody.html

* Jeremy D. Morley, an international family lawyer in New York, who works with family lawyers throughout the world. He is the author of two leading treatises on international family law, International Family Law Practice and The Hague Abduction Convention. He frequently testifies as an expert witness on the child custody law and legal system of Japan and other countries around the world.

Thanks for posting this excellent overview of an appalling situation that so many of us share. The point about excessively limited and supervised visitation being that way because ‘possession being all’ renders visitation periods of more than two hours highly susceptible to reverse abduction’, is a surprise to me. My understanding is that the first parent to abduct holds the power precisely because any reciprocal counter action is not viewed under Japanese law as abduction (which is not an offense), but as kidnapping, which is a serious offense carrying prison terms of 5 years+. Is it really true that a ‘kidnapping’ during a visitation is unpunishable, being classified not as a kidnapping but as ‘abduction’, which is not a crime? Readers new to the topic may wonder why left behind parents can’t simply approach their kids near their homes or schools? The kids are groomed by the abductor to believe that the left behind parent is violent and intends to ‘kidnap’ them. Stoked with fear such kids obey their abductor, ignore the left-behind parent, run away, or call the alienating parent who then calls the police alleging ‘stalking’, ‘harassment’, ‘violence’, or attempted ‘kidnap’. That’s of course assuming that the left behind parent even knows where their kid(s) have been abducted to.

LikeLiked by 1 person

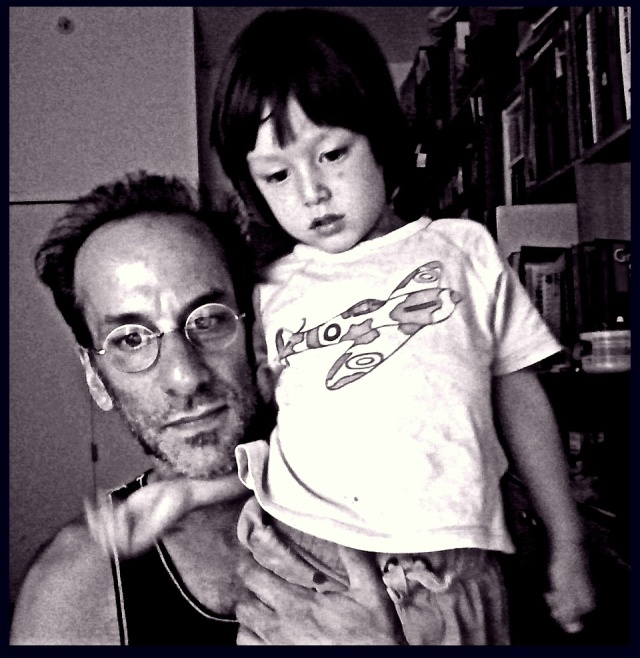

Thank you for the comments and for your thoughts. They’re very much appreciated. This is my reaction to the discussion here (and it’s absolutely not a negation of your contribution!) : I’m uncertain as to whether a distinction between a “legal abduction” and a “kidnapping” is something that’s really general or would be recognizable. The cognitive distortion among Japanese who abduct their children is such that they don’t apparently regard what they’re doing as “abduction” at all. They will ridicule (and have ridiculed) my use of the term, which is a strange experience to have when they obviously removed my four-year-old child and have permanently hidden him from me for seven years. But taking the child to an undisclosed address or to a grandparent’s home to achieve an eventual legal objective – which is physical possession leading rapidly to 100% exclusive custody of our children – doesn’t seem to have a name in Japanese society, aside from some obfuscation in common expressions like “taking the child home” or something similar. Tanase calls it abduction, as do some others; but this is the exception. The lack of precision, never arriving at definition, allows for the continuing mind-boggling blindness that they need for these child-abusive, rights-denying practices to flourish. It essentially allows them, in my opinion of this, to claim that *we* (parents who are victims of Japanese child abduction) are seeing a chimera and calling it “abduction”. But the law, inasmuch as there is any, allows a ministerial bureaucrat to assign custody to the person who comes to them with a family registry and a permanent address at which the child is being kept; that is to say, physical possession of the child is the only “continuity” that can achieve Japanese legal recognition. It’s an extremely thoughtless process, the evidence for which is how readily and easily it can be and is abused. But getting there requires thinking it through, a bit of strategizing on the part of the abducting parent. Once that’s been done, that is, once the child has been held out of contact with his or her other parent long enough, a few weeks or so, then the job is mostly done.

[In my case, the mother sought extra insurance against a challenge to what she had done (an international kidnapping, which may be a little bit more dramatic and conceivably harder to justify given the potential for there to be non-Japanese involved who are and were trying to get governments to make noise, less obligated by pressures of conformity) by taking my traumatized son to a pair of “doctors” and “psychologists” (who willingly collaborated with her by producing *atrociously* poor, transparent reports about my son. This was easily achieved as well: the trauma of being abducted at age four-and-a-half – suddenly finding himself without his Daddy around, and with his mother, aunts and grandparents all talking around him as if his father, to whom he was deeply attached, was gone for good – was just attributed to something inherently “bad” in the father. This was done in a purely speculative manner by people who never met me, never saw Rui with his Daddy, and wouldn’t have cared if they had, I don’t suppose.). But none of this really matters to a Japanese “family court” judge (who is little more than a bureaucrat).]

Once custody, which was never really in doubt, has been assigned, then any interference or “intrusion” from the children’s parent is, in the eyes of the Japanese law, equivalent to the intrusion of a perfect stranger. So taking the child home, or hanging out with the child at a playground, or going to eat or have a sleep over … these are construed as illegal, and no different from a perfect stranger doing them. I think this is what Morley is referring to and a point I’ve tried to make many, many, many times: child abduction and lack of visitation rights for children in Japan is entirely a *produced* phenomenon. Abduction is *induced* by the structure we’re talking about here. The parent who can successfully discern the high risk of losing the child to an abduction by the other parent first, is rewarded with… the child. And if a parent is more cautious, or holds onto hopes of relationship reconciliation with his or her spouse, or for a peaceful parting of ways without any nasty provocations (like, say, stealing or threatening to steal your child permanently away) then he or she loses. The first and most apparent route to the reward of not having your life destroyed by Japan is ruthlessness. As a result, parents abduct and bear the burden of that the rest of their lives, passing it on to their children.

It’s like Morley said elsewhere, the Japanese family law system is a maximally cruel game of “finders keepers, losers weepers.” Once an abduction has occurred, every contact with the other parent carries a very-much-maximized risk of kidnapping. After all, what loving parent could act completely within a strict and narrow range of “rationality” once his child has been taken from him, and it is all being treated as an unfortunate but nonetheless normal, everyday occurrence by an entire society, and the intruding friends and members of the child’s family?

In Freudian terms, it’s a situation that is ripe for “repetition compulsion.” But that’s another long conversation.

Thanks very much again, for reading and commenting.

LikeLike